I squeeze my eyes shut and try not to forget the day it happened.

The day my father’s kidneys quit.

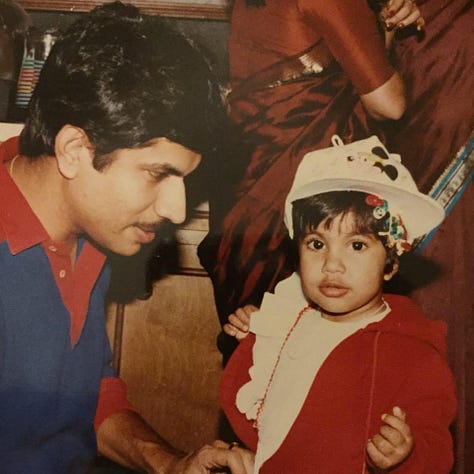

I am five years old, sitting on the stairs in our old split-level house. He is 34 or 35. I can see his face twisted in pain, arms wrapped around himself as though he needs to hold it all inside of his body—every organ, every ounce of blood, every thought, dream, desire. My mother seems to be teleporting from room to room. Making phone calls. Packing bags. Opening and closing the refrigerator.

Then time slows down. I watch her help him move through the door. As soon as his door closes, the car is gone—off to the hospital. I remember wondering what was going on. They didn’t have time to explain.

***

When you are experiencing acute renal failure, your kidneys suddenly stop being able to filter your blood. Waste can build up in your body, and blood can, for lack of a better phrase, get out of balance. You might feel nauseous, confused, fatigued, or weak. Your chest might hurt like a heart attack intersecting with acute sadness and anxiety.

If you’re lucky, young, and have something to live for, you could end up a transplant list. You’ll only have to endure dialysis for a few short months or years. And eventually they’ll cut you open, disconnect the two kidneys you have, and give you one good one.

One good kidney, still warm from the tragedy or trauma of another. When stress levels rise, adrenaline is produced, raising heart rate, body temperature, and even carbohydrate consumption. Still warm, then and maybe even a little hungry.

Pray that it’s an overachiever, this new kidney of yours—that it can do the work of two. Pray that it won’t quit on you or your body won’t try to kick it out—an illegal alien willing to come in and do the work that your own organs refuse or fail to do.

If you experience a rejection after an organ transplant, you might be ok. The rejection could mean your immune system is composed of Very Good Fighters. Or it might just be that your immunosuppressant drugs are falling down on the job. Get to the hospital quickly enough, and they’ll save that kidney while your body’s still warm.

***

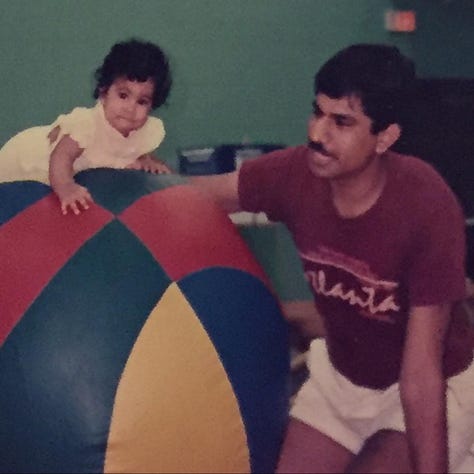

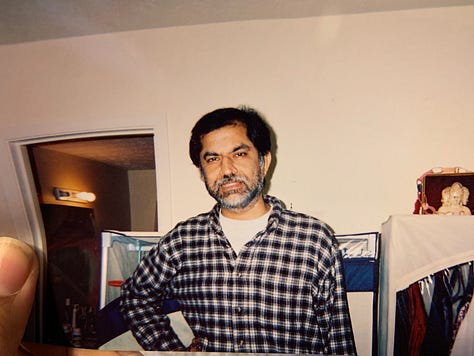

As far as kidney failure goes, my father had it easy. He was a young professional in corporate America with a beautiful young family. His job was flexible, and he drove himself to and from each dialysis appointment in his Honda Accord.

Three times a week, he’d sit in a moderately comfortable chair and let a machine clean his blood. For hours, he’d sit and listen to the machine while he crafted dad jokes and made small talk.

I imagine that the people around him became his friends—strangers forced into camaraderie because of their own lived tragedy. I imagine that if one of them stopped coming each week, they were hopeful that it was a transplant. I imagine they tried to quiet the anxious voice in their head—silencing the grief of the unknown.

***

And as the child of a chronically and terminally ill parent, I found familiarity in the sounds and smells of hospitals. The sound of pens clicking as doctors paused at the nurses’ station. The squeak of those rubber shoes, increasing in cadence and volume when a patient coded. The smell of latex gloves fresh from the box, of disinfectant as it dries.

Whenever those hospital visits happened, I learned how to pack the bag and put it in the car. I offered reassurances to Barbie dolls and stuffed animals that I would only be gone for a little while, and we would play more when I got back.

I became an expert at entertaining myself under stark, fluorescent lights—pushing quarters into vending machines, making small talk with the sweet nurses whose Southern drawl calmed my nerves, reading leftover Cosmo and Women’s Day and more tabloids than I’ll ever admit, watching Jerry Springer in unsupervised waiting rooms.

On especially long visits, or if my father would be staying for more than a day, I understood that we would stay with a family friend or a neighbor. It felt like a sleepover—eating casseroles in a house that didn’t know the touch of haldi in its kitchen, watching television and sharing a bed with my younger sister. We pretended not to notice the grown-ups exchange glances as we ate ice cream sundaes and explained the situation with words like nephropathy and ischemic.

***

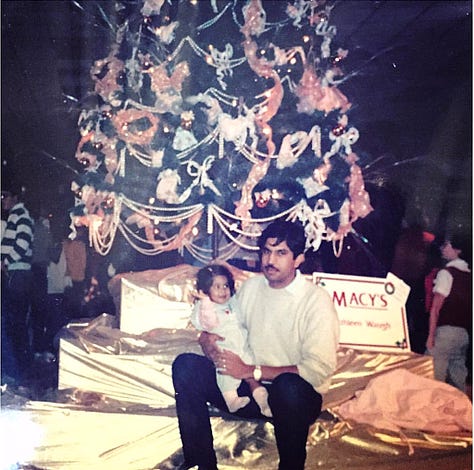

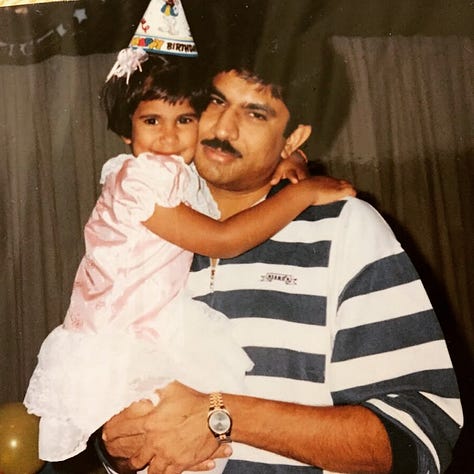

I once heard someone say that the gift of an organ transplant isn’t really the organ itself. The gift is time—giving someone the opportunity to live more years and make new memories. But my father’s time was fraught. Each new opportunity or glimmer of freedom would come with something new to chip away at his time from the other side.

The first successful organ transplant was performed in 1954 by a man named Joseph Murray. He performed the procedure on identical twins—taking a kidney from one man to save his dying brother’s life. The transplant gave them 8 more years together.

Rejection wasn’t a thing for them to consider. The histology and genetic compatibility were quite literally as favorable as they could be—it doesn’t get much better than identical. But not all of us have twins. Finding a compatible donor is essential to minimizing the risk of rejection.

Compatible donors, in some situations, are family members willing to live on one kidney, just like you. But more often, they’re young lives tragically cut short.

69 years later, Joseph Murray died in the same hospital where he performed that first transplant.

***

As I got older, my vocabulary became increasingly clinical. I knew the long list of medications he was prescribed, the specific types of doctors he was seeing. I researched every illness, every diagnosis. I found ways to connect all of my school assignments to the reading I was doing in my spare time. I was convinced I would become a doctor.

To this day, I still love academic literature. There’s something so satisfying about working through an article—the language so clean and precise—making sense of the author’s conclusions, and wondering how it’s being applied.

But in the midst of all this data, I never could fully grasp what my parents were feeling. I remember asking them what happened when we die. Sometimes they would shush me, move me along, and say it’s foolish and a waste of time to wonder.

Even so (and quite unfortunately), I’ve learned a lot about death in these 37 years—about the sudden loss of a friend and miscarriages rattling through my body, about watching an illness take the strength, the words, the desire, the breath from someone beloved’s lungs. I know what it’s like to see someone slowly wither in front of you. I know what it’s like to hear, “we’ve done everything we can.”

I know about watching the list of friends and loved ones you can’t call anymore grow. I know about deleting those phone numbers, grieving in this digital age as I scroll through old Facebook pages.

***

I know my mother believes in reincarnation. I don’t. More than once, she has wondered aloud why God will answer a prayer for a new handbag but couldn’t answer the desperate pleas for her husband’s healing.

I wonder now if she felt betrayed. The kidney failure was only the beginning. For fifteen years, she sacrificed tiny pieces of her American dream on the altar of my father’s health. She fasted and prayed through organ failure, transplant, stroke, epilepsy, mental health struggles, cancer, and more cancer. She offered fears and pleas in three languages to every deity imaginable. I wish I had understood.

Many days, my parents lamented the distance—lamented being disconnected from their families and homes. My mother often missed the voice of her mother in her times of greatest need.

I have never asked her if she feels robbed or resentful. I think I am afraid to ask.

But I suspect that if I had another person depending on me instead of having someone to share the burden of parenting and providing, I, too, would have complicated feelings on even my best days.

***

When studying about organ transplants, you’re likely to learn at least a little bit about immune memory. The immune system learns to quickly identify something it’s encountered before and respond the same way it did last time.

Our emotions, our hearts, adapt and respond like those T and B cells that recognize and respond to antigens and disease.

Perhaps love isn’t that different. We find someone compatible and willing to give of their time, energy, finances—willing to give you their best and worst years. Find someone that will minimize the risk of rejection. We recognize and reflexively respond to the good and the bad and the complicated. We experience love and safety based on what we’ve seen, what our bodies have known, before.

Sometimes love is slow and steady, uninteresting and predictable. But it doesn’t abandon you.

Love brings you home.

This post is part of a blog hop with Exhale—an online community of women pursuing creativity alongside motherhood, led by the writing team behind Coffee + Crumbs. Click here to view the next post in the series "Alive."

Beautifully told ❤️. What a lot you and your family have been through!

Beautifully written!